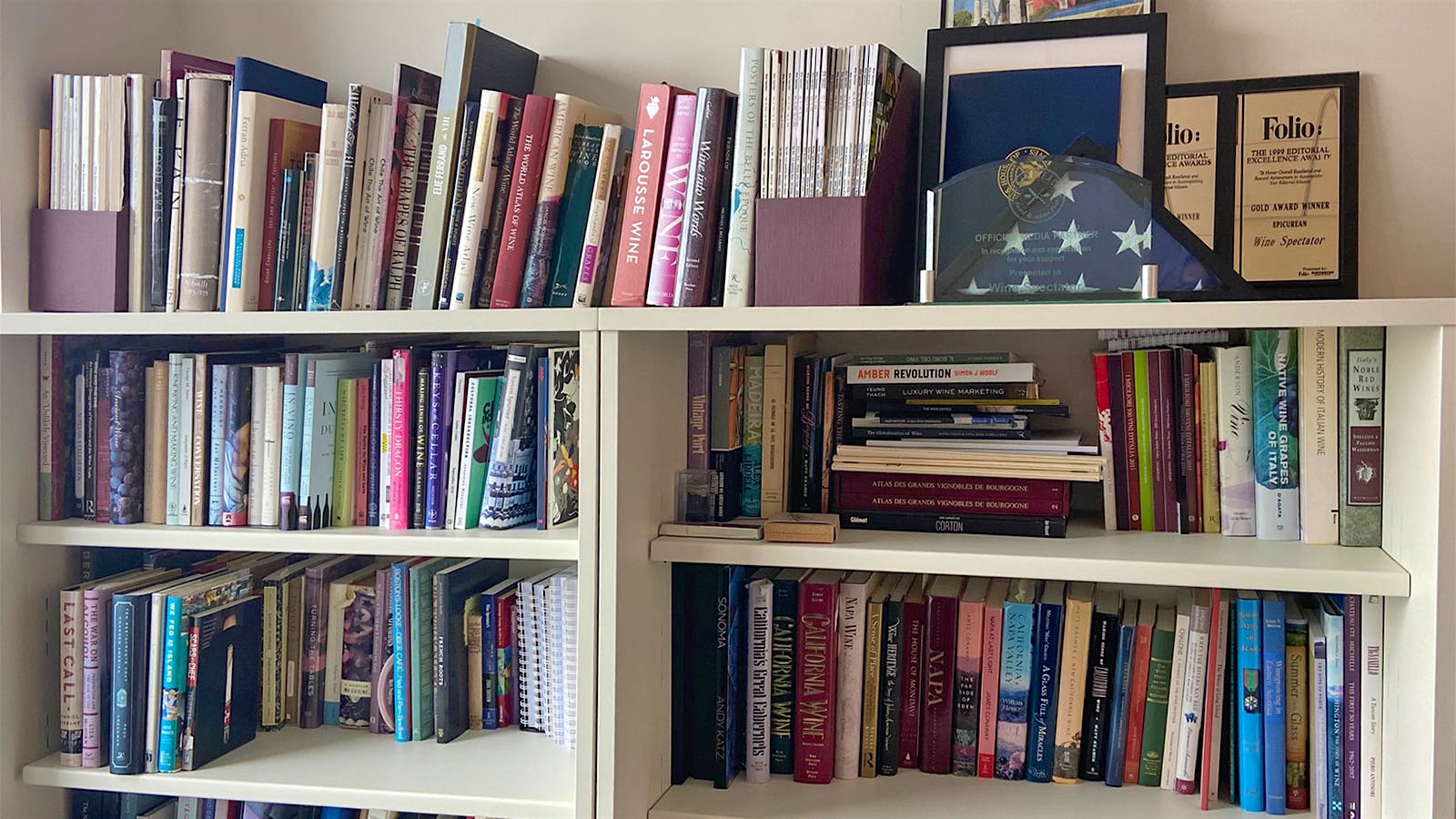

Over the course of four decades as a wine writer, I have accumulated a broad-ranging library of books about wine, food and travel. I keep most of them in my office, and it’s a frequent pleasure to scan the shelves, pull out a book and browse.

Libraries are personal; they reflect a reader’s taste, a worker’s needs and the chance acquisitions of gifts and random purchases. But most collections of wine books include a few broad categories: reference, history and memoir.

Here are a few books from each category that are part of my library. I value each for different reasons. I wouldn’t claim these are essential for every wine lover, but I hope they might be interesting in themselves, and prompt you to look again at your own library and how you might continue its growth and evolution.

Wine References

Oxford Companion to Wine, 4th Edition

Edited by Jancis Robinson

(Oxford University Press, 2015)

The World Atlas of Wine, 8th Edition

Hugh Johnson & Jancis Robinson

(Mitchell Beazley, London, 2019)

The Great Vintage Wine Book

Michael Broadbent

(Alfred A Knopf, New York, 1980, $8 at a second-hand bookstore)

Anyone who works in a research-based field needs reference books to answer questions, confirm facts and supply background information. I regularly consult encyclopedias and atlases.

The Oxford Companion is, in my view, the most comprehensive and the most relevant of the many encyclopedias available. A principal virtue is that its entries are supplied by dozens of contributors, all experts in their fields. For example, the entries concerning Spain, my main tasting beat, are mostly written by Victor de la Serna, a journalist for El Mundo and one of the leading authorities on the country’s wines. It’s worth it to upgrade to new editions as they are published.

The World Atlas of Wine has been a global success for decades. My first copy was possibly the first edition (1971). I used it as a road map when I was exploring Bordeaux in the early 1980s, and it rarely steered me wrong. Wine is intimately connected to geography, and this book made those relationships concrete in a manner both authoritative and beautiful.

The 8th edition is excellent, encompassing a much broader wine world than existed when the first was published. However, it can still feel a bit tentative. In Spain, for example, an excellent map details Rias Baixas, where the popular white Albariño is produced. But Jumilla is glossed over, despite its emerging potential to make complex, old-vine Monastrells. This is a big, slow-moving ship, and through every edition, it has moved in the right directions.

There has never been a more assiduous taster than Michael Broadbent, nor, likely, one with more access to great wines. This first edition of his Great Vintage Wine Book is a testament to and a celebration of great wines long gone.

The British author and auctioneer pays most of his attention to what may be referred to as the “classic” wines of the post-war period: Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne, Germany and Port. It’s a dream book for wine lovers.

Most of these bottlings I will never taste, but some I have tasted and find it instructive to compare my impressions with his. For example, he gives 1953 (my birth year) his top rating, 5 stars, and calls it “a personification of claret at its most elegant and charming best.” He offers several tasting notes for Château Margaux 1953, from the early 1960s to 1975, when he “noticed particularly its long fragrant aftertaste.” He suggested drinking it from “now” (1980) to “1993?”

I tasted this wine, along with nearly 1,000 other wine lovers, as the climax of a vertical tasting presented by owner Corinne Mentzelopoulos at the 1989 New York Wine Experience. The experience of that wine at that moment is one of the high points of my wine life.

Wine History

Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition

Daniel Okrent

(Scribner, New York, 2010)

Napa

James Conaway

(Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1990)

I am a history buff, and that interest is particularly appropriate to the subject of wine. The great wine estates and vineyards have long and rich histories. And a great wine only reveals itself through time. Sometimes a wine tasted half a century after its harvest can evoke an entire lost world. Like that Château Margaux 1953 tasted in 1989.

But there’s plenty of history outside the Old World. There are many terrific books written about Napa Valley, for example. William Heintz’s California’s Napa Valley (1999) is perhaps the most thorough and scholarly. The Wine Press and the Cellar, by E. H. Rixford (1883) is a time capsule that remains remarkably relevant.

James Conaway has delivered the most trenchant, riveting and polemical approach in a trilogy that began with Napa (1990) and also includes The Far Side of Eden (2002) and Napa At Last Light (2018). I’ve read them all and find this first installment the most enlightening. Its focus is the 1960s and ’70s, when today’s Napa came into being, and it centers on the environmental conflicts that remain at the heart of the valley’s cultural and political evolution. Conaway is too dogmatic for my taste, but his characterizations are dramatic and full of life.

Many books address the strange and turbulent period in American history known as Prohibition. I enjoyed Lisa McGirr’s The War on Alcohol (2016), which argues that the forces that led to Prohibition also tended towards anti-democratic, anti-immigrant and anti-minority movements. Daniel Okrent, a journalist and generalist, is a lively writer. In Last Call (2010), he turns this long struggle over alcohol into a vivid narrative about conflicts that are deeply embedded in American culture. Wine is more than the liquid in the glass; it reflects and affects our economy and our culture.

Travel, Photo Essays and Memoir

Wines and Castles of Spain

T. A. Layton

(Michael Joseph, London, 1959, $45 at a second-hand bookstore)

I have been a traveler, so my shelves are full of books by travelers, especially to wine regions. In fact, I wrote one of these myself (more on that later). A few years ago, I came across T. A. Layton’s Wines and Castles of Spain, and it’s a forgotten gem in the genre.

This first-person account of a voyage to Spain in the 1950s comes from a British writer who was “commissioned to write an encyclopedia on wine,” thought it needed first-hand research and decided to start in Cadiz. Layton may have published his encyclopedia; I have only found sketchy information about him. But this book is a quirky, personal and passion-infused story of his rather random travels around the country.

Layton presents himself as a babe in the woods, constantly confused by Spanish culture. But he muddles through, exploring castles and cathedrals, complaining about his hotels, and sampling tapas and churros. Wine is rarely the central topic, yet he takes it very seriously. He loves Sherry and Montilla (“the only great wine of Europe hardly seen in England.”) He finds himself in Priorat 30 years before its modern revolution, and says its wines “are of a definite style and have some character.” Reading it placed me very vividly in the life and culture of an older world.

The Carmenère Wines of Chile

Photography by Sara Matthews

(Vina Concha y Toro, Santiago, Chile, 2007)

A Village in the Vineyards

Thomas Matthews, photographs by Sara Matthews

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1993)

Wine regions on the whole are remarkably beautiful, and many photographers have specialized in their landscapes, architecture and communities. Alain Benoit on Bordeaux, Jon Wyand on Burgundy and Andy Katz on California are standouts.

My wife, Sara, has been a wine photographer since the 1980s and developed a specialty in South America, which she has visited dozens of times. Her photo essay on The Carmenère Wines of Chile is a beautiful portrait of a distinctive culture.

This grape was a gift wrapped inside a mystery. The roots of Chile’s contemporary wine industry date to the mid-19th century, when local aristocrats imported French grapes and wine technology. Carmenère, then common in Bordeaux, was one of the imports. But when the variety vanished from Bordeaux, a casualty of phylloxera, it was somehow erased from memory in Chile, harvested in the disguise of Merlot. Only in 1994 did vine scientists realize that Carmenère was both abundant and successful in Chile.

Concha y Toro, Chile’s largest winery, decided to showcase this overlooked grape. The company hired Sara to create a photographic essay that would testify to Carmenère’s authenticity and its distinctive character. She focused not only on the vineyard, but also on the broader landscape, the people who lived and worked in it, and the culture that it reflected. The result is a work of visual anthropology that delivers both information and beauty.

Sara was also the photographer for my book, A Village in the Vineyards, published in 1993. It recounts our experiences in Ruch, a small wine community in Entre-Deux-Mers, a backwater of Bordeaux. Though the adage claims you can’t judge a book by its cover, that’s not true in this case. If the image of a church steeple rising above old vines doesn’t appeal, you probably won’t be interested in the text.

My goal was to sketch a portrait of a culture deeply rooted in the past and struggling to adapt to the changes of onrushing modernity. We loved the community that welcomed us—the Socialist mayor, the crusty farmers, the workers at the wine cooperative, the old ladies who gossiped in the local store. We made friends for life, and still return from time to time, happy that Ruch has prospered without losing its character or its soul.

Like a bottle of fine wine, a good book takes us on a voyage to a particular place and time. It’s an artifact, but also a message that can build a bridge from our lives to a wider world. Whether on the page or in the glass, wine opens the doors of perception. For true wine lovers, both the cellar and the library are keys to the good life.