The dog days of summer invariably send this wine canine (me) in pursuit of a favorite treat: summer reds to serve chilled, paired with food off the grill or with cool salads.

The latest on my list of Italian summer cravings is Ciliegiolo, with its red fruit flavors, soft tannins, deep ruby color, bright acidity and spicy aromas.

Planted across Tuscany and a wide swath of central Italy, Ciliegiolo is one of those old blending varieties now coming into its own. Its secondary role in Chianti Classico and other wines was traditionally to support Sangiovese—Tuscany’s red star and Ciliegiolo’s genetic relative—by adding intense color and soft tannins.

Many Sangiovese-proud Tuscans now producing Ciliegiolo refer to it as a fun wine that fits current drinking styles. But I think Ciliegiolo is more than that. In the right hands and from the right places, it can be gorgeous.

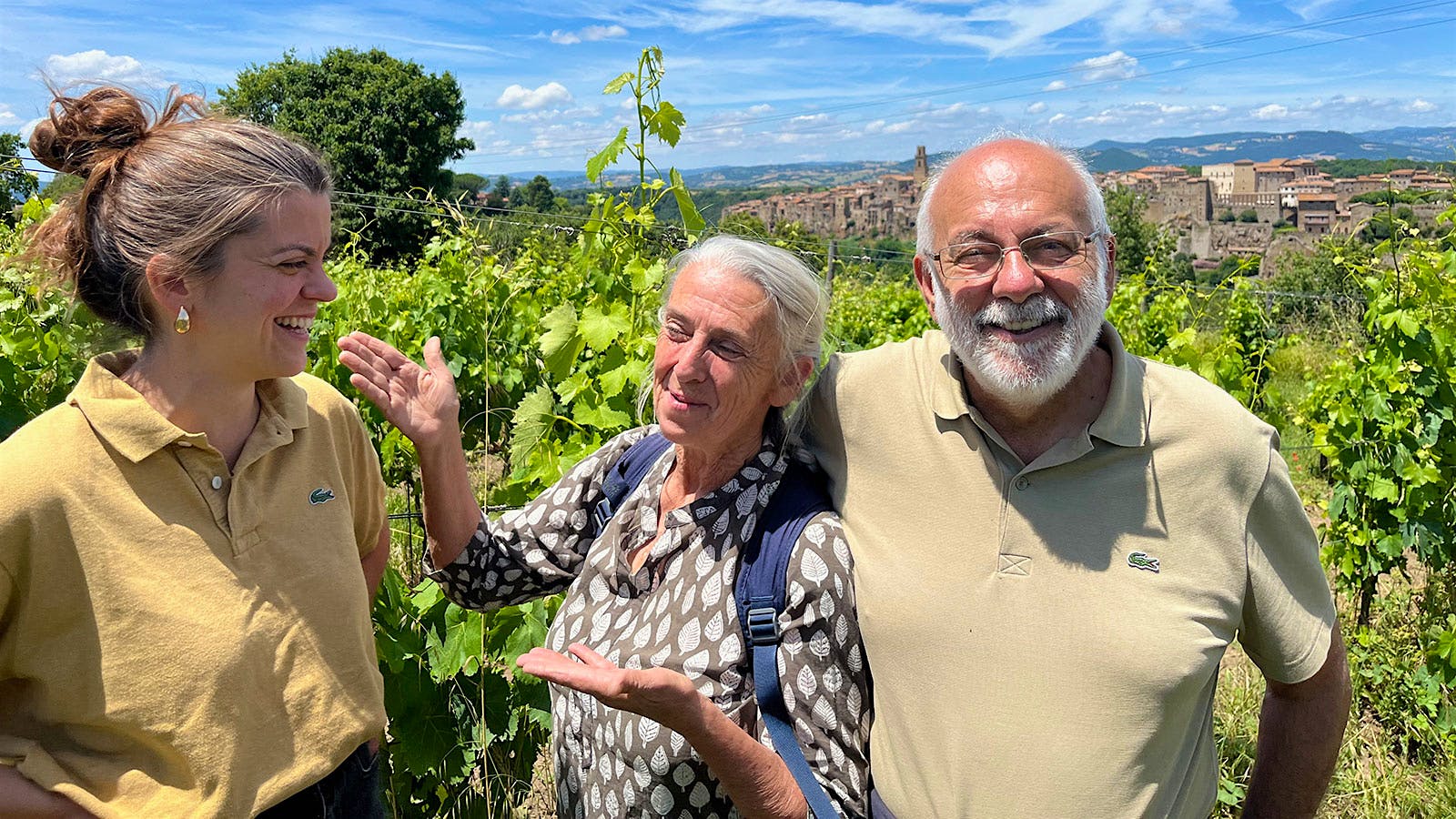

“We fell in love with it,” explains Edoardo Ventimiglia, 69. He and his agronomist wife, Carla Benini, 66, are pioneering, longtime Ciliegiolo growers at their Sassotondo estate in southern Tuscany’s Maremma region.

The Maremma, which spans an area from the Mediterranean coast to the volcanic tuff hinterlands where Sassotondo lies, is the center of Ciliegiolo’s impassioned revival. With little of the wine tradition of the vineyards around Florence, farther north in Tuscany, the Maremma is a modern stepchild best known for white Vermentino, red Super Tuscans and experimentation.

Before falling in love with Ciliegiolo, the couple fell for a largely abandoned 180-acre farm with a farmhouse, a sheep barn and a couple of acres of vines planted in volcanic soils at an altitude of about 1,000 feet. Benini’s family bought it in 1990 for less than the equivalent of $750 an acre.

In the early 1990s, the couple lived in Rome. Ventimiglia was an urbane, third-generation cinematographer, and the couple spent weekends in this patch of countryside, working the land organically and selling their grapes to the local cooperative.

“It was super wild,” recalls Ventimiglia. “There was no electricity until around the time our daughter was born in 1993.”

About that time, their grape obsession began. They found and bought an old nine-acre Ciliegiolo vineyard a few miles from their farm. Known locally as “San Lorenzo,” it covered a volcanic tuff ridge dramatically looking over a small valley to the ancient hilltop town of Pitigliano.

Within four years of that purchase, they quit their careers, moved to the farm with a preschooler in tow, and started making their own Ciliegiolo in the old, vaulted cellar dug into the hillside.

Finding Ciliegiolo's Strengths

Benini had been impressed with the way the Ciliegiolo seemed to withstand punishing heat during the growing season while Sangiovese and other vines seemed to wilt.

“If I have a good feeling about a plant, it works for me,” she says with wide-eyed enthusiasm. “And Ciliegiolo is beautiful, happy in the heat, generous, resistant to disease … and the grapes are delicious right off the vine.”

The courage to take the leap was boosted by their Tuscan consulting enologist, Attilio Pagli, who had been making varietal Ciliegiolo wines for nearly a decade at coastal Maremma’s Rascioni & Cecconello.

“He was the first to believe in Ciliegiolo,” Ventimiglia says. “At the time in Maremma, the mantra was ‘Cabernet-Merlot, Merlot-Cabernet.’”

To bring out Ciliegiolo’s best, the couple worked with Pagli, experimented and visited producers of fine lighter-bodied reds from Piedmont to Beaujolais to Burgundy. “Ciliegiolo is elegant, and it has structure but it expresses itself delicately,” Ventimiglia notes.

Because the variety is a naturally productive workhorse, the couple dramatically scaled back vineyard yields. In the winery, they pursued delicate whole-berry fermentations with indigenous yeasts and used minimal extraction techniques.

Sassotondo’s Ciliegiolo wasn’t an instant fairy tale. In Italy, their wine was born as a mild curiosity. Abroad, it quickly found a small California importer, but that trade dissolved in the wake of Sept. 11, 2001.

Despite all the ups and downs, including challenges such as wild boar and extreme storms and hail, their business has taken off in the last five years, riding a wave of lighter-bodied reds.

Today, they cultivate 34 acres, half of it Ciliegiolo. Sassotondo produces a total of about 4,000 cases spread across 13 red and white wines, including several blends of Italian and international varieties.

Five of the wines are pure Ciliegiolo. In addition to an entry-level Ciliegiolo from vines on their farm and San Lorenzo, they make the cask-aged “Monte Calvo” from a plot in San Lorenzo, the amphora-fermented and -matured “Poggio Pinto” from a 25-year-old plot on their home estate, and the “San Lorenzo,” their richest wine, made from a vineyard selection aged in large oak casks. They also make a surprisingly juicy, dark and mouth-filling Ciliegiolo rosé called “Lady Marmalade.”

A Small But Mighty Force in and Beyond the Maremma

On a Saturday morning, in the old 12th-century castle of nearby Sorano (pop. 3,000), I sampled dozens more wines at a Ciliegiolo tasting hosted by the Maremma Toscana wine appellation. It mostly featured Maremma producers—from New York celebrity restaurateur Joe Bastianich’s La Mozza to Tenuta Belguardo, the Maremma estate of the Mazzei family of Castello di Fonterutoli fame in Castellina in Chianti.

Francesco Mazzei, co-CEO of Mazzei and president of the Maremma wine consortium, notes that a mere 1,000 acres of the Maremma’s 23,000 acres of vineyards are planted to Ciliegolo. “It’s a contemporary wine,” he says. “It’s pleasurable and easy to drink. The key is the pleasure.”

Other Ciliegiolo producers hailed from elsewhere in Tuscany and across central Italy up to coastal Liguria. From locale to locale, Ciliegiolo shows subtle-to-distinct differences in body, texture, flavors and aromas, which vary from Mediterranean spice to licorice to eucalyptus.

“Ciliegiolo is a great marker of terroir,” says Leonardo Bussoletti, Ventimiglia’s friend and president of the Ciliegiolo di Narni producers’ association in Umbria.

Bussoletti, 55, a former wine salesman, began making wine 20 years ago, working with the University of Milan to select 30 Ciliegiolo biotypes. Today the main main market for his wines—five varietal Ciliegiolo bottlings and one Ciliegiolo blend, totaling 2,500 cases—is New York City.

“Manhattan and Brooklyn!” he exclaims.

He wears a polo shirt and, as he lifts a glass, a tattoo on the inside of his bicep appears, affirming his commitment.

“#Ciliegiolo” it reads.

“Ciliegiolo,” he says with a grin, “is my life.”